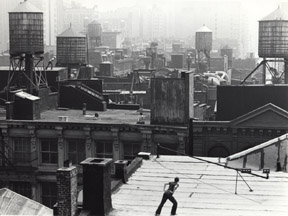

| About Roof Piece | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How I Made Some of My Films | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Making of Water Motor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Living Somewhere | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Collecting as a Creative Process (coming soon...) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the Making of Water

Motor, a dance by Trisha Brown filmed by Babette Mangolte It was winter 1978 and Soho was still a quiet place mostly habited by artists who all knew each other and were far from imagining the commercial mecca that it is now. Walking in the street you met your friends. And it is what happened on that winter day when by accident I met Trisha in the street. She told me that she was working on a new solo and was very happy about it. I proposed to come and see it and she said: “Come anytime’s. I am doing it every day. Just call when you are ready”. In 1978 I was the semi official photographer of the Trisha Brown dance company and knew her dance vocabulary very well. I knew she was preparing new work for an evening at the Public Theater on Lafayette Street where she would be performing for the first time. I was looking forward to it. I always like to see what I am going to photograph before the actual photography session and avoid arriving at the dress rehearsal without preparation. So one day I went to scout Trisha’s solo at her loft, curious about the new work. She had named the solo Water Motor and it was short at about four minutes. I was stunned when I saw it. Not only was it absolutely thrilling but I also felt it was an enormous departure from the movement in her previous piece Locus. Somehow you could hardly see the movement (dance) because it just went too fast. It was totally new. It is that strong first impression that the new solo was the beginning of a new phase in Trisha’s work that triggered in me the desire to record it on film. Because of the dance sheer bravado and speed I also felt that the physical abilities of the dancer had to be so fine-tuned that maybe Trisha would not be able to dance it for many years to come and therefore the film recording of it was urgent and should not be delayed. Although Trisha laughed at my fear that she was not going to be able to perform it for many more years she agreed that I could film it. As a filmmaker I knew that dance doesn’t work with cutting and that an unbroken camera movement was the way to film the four-minute solo. I had learned it by watching Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly’s dance numbers. Somehow the film camera has to evoke the hypnotic look and total concentration of the mesmerized spectator and fragmenting the solo in small pieces taken from different camera positions would break the spectator’s concentration and awe. I also knew that Trisha could dance the solo twice in one day maybe three times but no more, so in filming it, I had no room for lengthy rehearsal of the dance to practice my camera work. I had to do well the first time. So I decided that I would learn the dance and have it so much in my head and brain that I would follow the dance with the film camera with no effort on the day of the shooting. I proceed to do that by going to Trisha’s loft twice a week for about three weeks so I could learn the dance. It is in the course of that practice that I did some photographing of the solo and took one of my best photographs, which I felt was encapsulating what was so mesmerizing about the movement, a photo where you feel that Trisha is moving in two contradictory directions at the same time as if half of her body is going left when the other half is going right. For the shooting I rented the Merce Cunningham dance studio where I had a clean background, good floor and a grid with lights. When I was doing the lights Trisha could warm up and mark the space for me and for the lights. That took a little less than one hour. Trisha’s marking the space just indicating the movement permitted me to set up the camera position and height that I had already conceptualize while learning the dance in the preceding month during rehearsals. Then I shot the solo twice and felt that my camera moves were competent

and Trisha was also happy about what she had done in both takes.

I felt that one of the take would be the one to use and I had coverage

in case of a problem that I had not foreseen. Because I was happy

with my camera work I could risk another third take that Trisha

was willing to do. It is then that I took the gamble to shot in

slow motion just to discover the movement in a less impersonal and

more interpretative way. I just wanted to see the movement slow

down to understand it better and but also to see something you can’t

see any other way. The only thing I feel sorry about is that I didn’t have the money to shoot with sync sound. The solo was silent anyway and performed with no music. But a silent film does not create the impression of silence. It is sound film that has created silence in motion picture. But if I had had a sound sync camera it is likely that the camera motor would have been only running at sound speed and therefore I would have been unable to shoot slow motion unless I had planned it prior to the shoot. That fortunate decision of using slow motion came on the spur of the moment and I think it is what makes the film of Water Motor so distinctive, that and the virtuoso movement, elegance and grace of Trisha Brown. The best praise came for me when Yvonne Rainer, a close friend of Trisha, a great choreographer herself and who admired the film of Water Motor quoted the film in its entirety in one of her own films. 1 Much later in 2000 at a benefit for the Trisha Brown Dance Company, where the film was included in the program, Trisha spoke publicly of the fact that she had accepted reluctantly to be filmed. Although the solo is still in repertory Trisha dances now a version that incorporates some of the original movement with another dance “with talking” and relies on an improvised voice track (often hilariously funny) and the radio mike used for the voice also transmits the body movement and breathing of the dancer. Most of the 1978 movement has disappeared. It isn’t the same dance. I now think that for a dancer to commit to eternity the way you moved on a particular day is risky. 1The film is The Man Who Envied Women © 1985 Yvonne Rainer |